What's Valuable Now May Become Valueless--and Vice Versa

You are receiving this post because you are a subscriber to Charles Hugh Smith / Of Two Minds.

If extremes exhaust themselves and revert to the mean, if cyclical highs slide to cyclical lows, and if the pendulums of human emotions and certainties swing slowly from one extreme to the other, then what's considered valuable now will become valueless and what's considered of low value now will become valuable.

In summary: The way of the Tao is reversal.

What's considered valuable now? Financial assets and the casino of trading them. This mania began 30 years ago, in the first Tech Bubble of the late 1990s, when online trading platforms (eTrade, et al.) enabled everyone to trade securities for minimal fees without having to call a broker to handle the trade, and stories of admin assistants becoming instant millionaires when their tech employer went public (IPO--initial public offering) circulated.

A friend who worked at Oracle at that time related that employees were trading stocks in their mid-day break, making a few quick trades to pay for lunch.

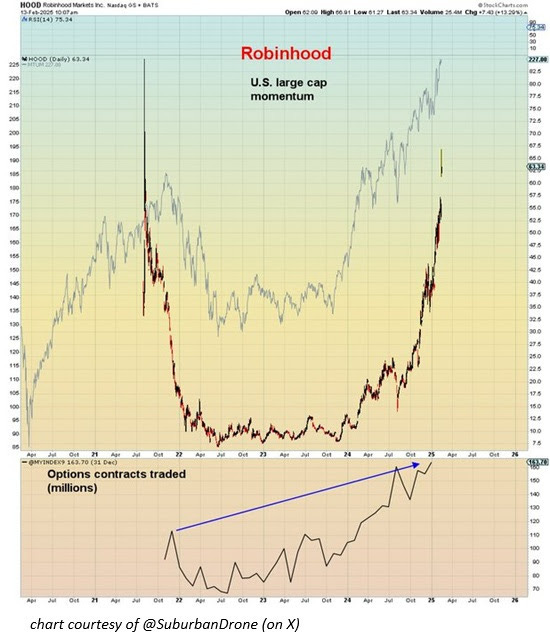

This mania has now reached extremes as it has become mainstream: options, once a security traded mostly by professionals as hedges, are now the financial trade of choice as they offer the greatest leverage and risk/return. This chart of popular smartphone-trading platform Robinhood (take from the rich and give to the poor via trading securities) shows the dominance of trading options as the means to "beat the house" in the trading casino. (Options expire, so it's easy to lose the entire bet.)

The opportunity arose in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Meltdown to rein in the speculative mania, but authorities chose to double-down on making speculative trading of financial assets the most compelling way to make a fortune and escape the increasingly arduous treadmill of the workaday world.

Now 15 years later, this speculative mania is no longer a mania, it is simply everyday life: it is no longer recognized as an extreme of speculation and certainty that will revert to the opposite end of the spectrum.

What is the certainty? Simply this: there's a Bull Market somewhere. The trick is to hopscotch from one Bull Market to the next, and continue doing so until the end of one's life, because why stop making money so easily?

That this is not certain is not recognized, as the past 30 years have proven that there's always a Bull Market somewhere. Just move to another table in the casino.

What makes something valuable? We have several stock answers. Demand makes something valuable: something increases in value if people want it. Scarcity: it's rare, so it increases in value. So people want to live in a nice neighborhood, the number of houses in the neighborhood is limited, so the value of the house rises 10-fold over a generation.

Money in all its forms is intrinsically valuable, as we can use it to buy assets, goods and services. Money is also a tradable commodity, so another way to get rich is to trade currencies and various forms of money: gold, bitcoin, etc.

All this is self-evident. Or so we think. But we're thinking of money and value in the casino, which is now the entire world. Or so we think. But there is a world outside the casino where value is measured in ways that cannot be reduced to a price tag or profit from a trade.

In a recent podcast with LeafBox (on Substack), Robert asked me to explain my recent experiments with reducing our electricity consumption. Interview: Charles Hugh Smith - Spring 2025.

The idea was simple: how much could we reduce our consumption of electricity with behavioral changes and a relatively modest 1500 watt battery / 400 watt solar array?

The goal was to reduce our consumption without reducing any of the comforts and conveniences afforded by electricity: no sacrifices were made, we retained every comfort and convenience.

The essence of the scientific method is to isolate the variable you wish to study, design an experiment, collect data, and then observe what changed or didn't change. Then run another experiment. The process is incremental.

The variables here were 1) how much electricity could we generate and store and 2) how much could we reduce consumption by making behavioral changes?

Our main behavioral adjustments were 1) avoid wasting electricity and 2) turn the electric water heater off after an hour. Since we lived on water catchment for a time, we keep showers short and don't waste water, and since modern water heaters are well-insulated, the water stays hot enough for all uses the next day.

(We consume 1,500 gallons per month, 300 gallons of which are used on our vegetable gardens. The average household in the state uses 9,000 gallons per month, and about half the households use under 6,000 gallons per month. So we consume between 25% and 17% of the average household.)

We reduced our consumption of utility-provided electricity by 20%. We now consume about 4.5 kilowatts a day, compared to the state average of 16.3 KW a day, so we use about 28% of the average household. In addition to the electric water heater, we also use high-consumption power tools (13 amp Skilsaw, heat-gun, etc.) We generate and consume about an additional 10% of this consumption with our modest solar array.

What's valuable here? Let's start with comfort and convenience, which we "price" by the cost of the electricity and appliances. But comfort and convenience don't distill down to the price, as we would pay a lot more for some and abandon others if the cost soared.

Internet service is now an essential utility just like water and electricity, and so I rigged our modest solar generator to power our electronics: laptops, modem/router, printer, etc. These are now off-grid.

The idea here is to experiment with how large my own private utility must be to run the Internet, lighting and a refrigerator if the grid goes down in a major weather event.

The experiment's purpose is to right-size my own utilities to the minimum required to maintain all the comforts and conveniences of modern life. Maybe a costly rooftop solar array and big battery aren't necessary.

It's worth noting that many solar-rooftop arrays serve the local utility; the homeowner has no way to tap the electricity being generated by their own PV panels.

This raises another question: in terms of use-value, what do you actually own and control 100%? What's the value of things you nominally own but that are dependent on / controlled by others?

What's the value of owning one's own modest electrical utility? We can state this another way: what's the value of a kilowatt? When the utility is providing the power, the cost is very low in much of the nation: 11 cents, 15 cents, 20 cents. But how much would you be willing to pay for a kilowatt after two days without electricity? How about after five days?

Demand and scarcity: when the water and electricity are no longer flowing, we still need them but they're now unavailable.

You see the point: the value of things can change very dramatically and is not as predictable as we assume. It's impossible to "price" the use-value of things we need prior to an event that dramatically changes demand and/or scarcity.

Food is something else we assume will always be abundant and if not cheap, far cheaper than in many places around the world, where households spend 40% or more of the family income on food.

What's the value of growing some of your own food? When the supermarket shelves are full and prices stable, we turn up our noses at those gardening and tending home orchards. Why bother doing all that work when the "value" measured in money of the produce is so modest? Why spend an hour gardening to grow $5 worth of vegetables when you could have made $25 working and bought five times the amount of produce you grew?

This perspective assumes value can be equated with price. But growing food is a good example of how this equivalence is misleading. We know nothing about the nutritional content of the food we buy at the grocery store. Even buying organic produce tells us nothing about the soil or trace nutrients; organic simply means no pesticides or herbicides or chemical fertilizers were applied. This doesn't automatically equate to nutrient-rich soil or nutrient-dense produce.

The long-term decline in the nutritional content of food has been quantified, and we're told the "solution" is to "take a supplement." But studies have also found supplements don't replace real food. Many studies have found supplements have little to no value in terms of increasing our uptake of trace minerals, as this process isn't like a machine: taking a pill doesn't mean our bodies will absorb the minerals the way a computer transfers files. It's far more complicated than the mechanistic model we apply to virtually everything.

So what's the value of knowing what's in your soil and thus in your food? What's the value of connecting to the earth and the joys of harvesting what you've grown?

There is no "price" that can be assigned to these qualities. To even attempt to do so reveals the absurdity of how we reckon value in financial terms.

CHS NOTE: I understand some readers object to paywalled posts, so please note that my weekday posts are free and I reserve my weekend Musings Report for subscribers. Hopefully this mix makes sense in light of the fact that writing is my only paid work/job. Who knows, something here may be actionable and change your life in some useful way. I am grateful for your readership and blessed by your financial support.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Charles Hugh Smith's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.