Orwellian, Kafkaesque, or Both?

This is the unifying theme of Kafka's The Castle: we're imprisoned by our acceptance of and belief in a power structure.

This is Musings Report 2023-45.

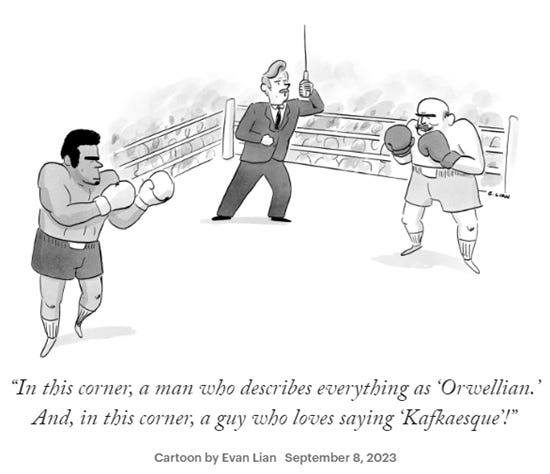

This New Yorker cartoon captures the current zeitgeist: "In this corner, a man who describes everything as 'Orwellian.' And in this corner, a guy who loves saying 'Kafkaesque'" In a three-way match, we'd include the other favorite prognosticator, Brave New World's Aldous Huxley.

I'm certainly guilty of invoking Orwell, Huxley and Kafka to describe aspects of the present distemper. I'm reading Kafka's last novel, The Castle, and it's broadening my understanding of 'Kafkaesque.'

Kafka is known for his story of exclusion, The Metamorphosis, in which a man awakens to discover that he's been transmogrified into a 6-foot cockroach, who is now treated with revulsion.

His novel The Trial establishes many of the themes we consider Kafkaesque: a hidden, capricious power whose actions and intentions are obscure; the complications of romantic / sexual attractions / relations, the inherent ambiguity of the circumstances, and the flailing powerlessness of those subject to the capricious power.

All of these are also elements in The Castle. I last read Kafka decades ago in school, and what strikes me in this current reading is its dream-like nature.. As in a dream, each scene is set with a few details, and the protagonist is frustrated at every turn; there is no narrative per se, just a series of frustrating dead ends. For example, the protagonist K. starts up a road which he expects will take him to the castle, but it leads back to the village.

Also as in a dream, characters appear and do things and say things which don't serve a conventional plot narrative. K. attempts to make sense of these interactions but is left uncertain about the intentions of the character. K.'s goal is to gain access to the castle to clarify his employment status and gain approval to marry his new lover in the village, but this proves impossible.

There are many such dream-like elements. The bureaucrats in the castle are both numerous and busy; when you call the castle on the phone, you hear a background buzz of constant telephone calls going on. Yet you don't know who answered the phone, as the bureaucrats typically don't bother answering calls from the village; they only take calls as pranks or randomly, and you might get an anonymous clerk in a division who mishandles your request.

In other words, very much like dealing with the IRS or the California DMV. I spent months a few years ago trying to get these agencies to do very basic things: change my address, and register a vehicle in storage. The process required constant correspondence with anonymous clerks, correspondence that twisted and turned but never reached the intended goal.

Where Orwell describes an oppressive authoritarian nightmare, Kafka describes the dream-state of confusion and frustration: you forgot to go to class and so you'll miss the final exam, you can't reach your destination, you're in a maze of streets and can't get home, etc.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Charles Hugh Smith's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.