China Adrift: Now Is the Winter of Our Discontent

You are receiving this post/email because you are a patron/subscriber to Of Two Minds / Charles Hugh Smith. This is Musings Report 2024-34.

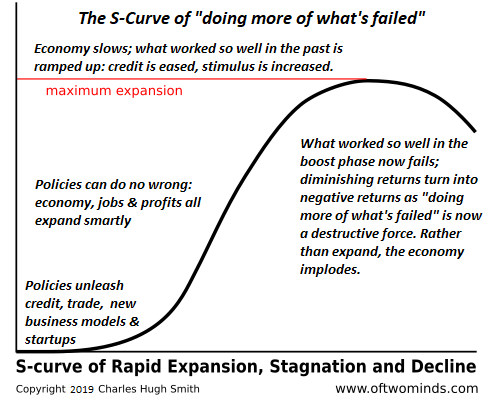

Every economy, no matter how robust, experiences periods of expansion and malaise that manifest as enthusiastic confidence in the heady boost phase and demoralized discontent in the exhaustion phase. I have often used the S-Curve to map this recurring pattern in economies and in Nature.

The United States went through such a period of discontent and malaise in the 1970s, an era I've described as being misunderstood as an ultimately positive phase of long-term investment and adjustment to new realities.

In the S-Curve, the boost phase is expansive because policies and current conditions fuel a self-reinforcing dynamic. The conditions for expansion are present--low-cost credit / savings to invest, people to house, feed and put to work, global markets willing to import surplus production, ample natural resources, geopolitical peace--and policies that incentivize and reward expansion are in place.

The rapid growth is infectious, and public confidence in a better future are also self-reinforcing: as hard work and sacrifice ("eating bitter tears") are rewarded with rising prosperity and prospects, anything seems possible--not in a distant future, but right now.

In this boost phase, the low-hanging fruit is just waiting to be harvested, and those who scramble ahead of the crowd reap the windfall and become rich. In the glorious boost phase, the low-hanging fruit seem endless, as if there will be plenty for everyone.

But nothing is limitless, and once the low-hanging fruit has been plucked, diminishing returns set in: all the easy windfalls have been exploited, and what's left is barren soil that requires investing more capital and taking on more risk--risk that goes unrecognized, because everyone has become accustomed to easy, guaranteed gains.

Since everything is running smoothly, there's no impetus to change policies: why risk messing up what's been working so splendidly? There is also no incentive to look for evidence that the engine of growth is sputtering. Rather, there are powerful reasons--for example, recency bias--and financial and emotional incentives to dismiss or paper over signs of diminishing returns as mortal threats to a status quo that has boosted everyone's prospects and hopes.

This is how the status quo ends up doing more of what's failed: since the policies worked so well in the boost phase, the answer to diminishing returns is to do more of what worked so well in the recent past. If loosening credit greased the astounding expansion, then the solution to a slowdown is to loosen credit even more. If subsidies and stimulus worked beautifully, then the solution is to expand subsidies and stimulus.

The problem is that the policies only worked in conjunction with the conditions, which have now changed as a result of the rapid expansion. The low-hanging fruit has been picked, the easy profits booked, the consumer demand has been met and exports have reached every corner of the globe.

The mighty engine has consumed the available fuel, and so throwing gasoline on the embers no longer creates growth, it generates systemic hazards, as loose credit and subsidies encourage the moral hazard of high-risk investments in marginal projects that become tottering dominoes in the financial system.

That there can be too much of a good thing is not in the public consciousness in the boost phase: growth seems endless, and endlessly positive. Ramping up the production of highly educated workers by building hundreds of universities, for example, boosted productivity and growth in the expansion phase, and so graduating ever larger classes of graduates seemed like an unbeatable strategy for boosting expansion.

But eventually the number of graduates swamps the number of jobs requiring a university degree, and the graduates who can't find jobs form a discontented surplus elite.

Demographics can also become less constructive after a generation of expansion, as prosperity tends to reduce the birthrates and older workers retire, becoming dependent on government pension and healthcare programs.

Everyone from workers to students to retirees to policymakers assumes that the trajectory of growth is now a permanent feature of the economy, and so plans are made based on limitless expansion.

But eventually, doing more of what's now failing pushes diminishing returns into negative returns, and doing more of what worked so well in the past now increases the risk of failure as overindebted companies who sunk borrowed money into marginal projects go bankrupt, workers who counted on lifetime employment are fired and other workers who expected raises find their wages have been cut.

Policymakers are flummoxed, as everything they're doing more of has either little effect or it generates negative consequences that the system is not set up to handle, as the system was optimized for rapid growth. Now that the economy is sliding down the backside of the S-Curve, the system is accelerating the stagnation by doing more of what optimized expansion in the boost phase.

When faced with stagnation, policymakers' first instinct is to increase their control of the economy as a means of arresting the decline: imposing new standards and punishments, pushing new subsidies and stimulus, exhorting business and workers to spend more money to boost consumption--all of these end up increasing the sense of ennui and malaise, as it's clear none of it is working as intended.

The ship of state is adrift and the public mood has darkened; the mood is resigned, disgusted, demoralized, and phrases such as "the Garbage Time of History" gain widespread use.

This brings us to China.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Charles Hugh Smith's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.